Muslims Schools in U.S. a Voice for Identity

By Susan Sachs

New York Times - November 10, 1998

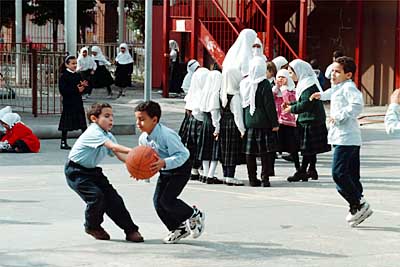

The playground at Al Noor School in Brooklyn. The principal said 400 students were turned away for lack of space at the 600-student school. |

The school year is already in full swing and still the parents come, crowding into the principal's office at Al Noor School in Brooklyn, painstakingly filling in forms, proffering checks and pleading in Arabic and English for a chance to enroll their children in the New York area's biggest Islamic private school.

"We turned down 400 kids because we don't have space," said Nidal Abuasi, the principal, whose resources are already stretched to accommodate Al Noor's 600 students. "We have people who come hoping we have space even if their child has to be demoted to a lower grade. There is a huge demand."

Across the country, Islamic schools like Al Noor that offer religion and Arabic classes along with a standard academic curriculum are expanding and flourishing, with many becoming oversubscribed so quickly that principals are scrambling for money to build more.

The reasons for the surge are as diverse as the American Muslim population itself, which embraces American-born converts and a swelling immigrant population from Asia, Africa, the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent.

But the educational structure these schools have forged -- prayer, discipline and American-style teaching -- has an appeal that cuts across lines of national origin and background.

At Al Iman elementary and high school in Queens, as at the 23 other Islamic schools in New York City, Long Island and New Jersey, the day begins with prayer: rows of children, separated by sex, reciting in Arabic the ancient words of submission to Allah.

Posters of Islam's most famous mosques and the sayings of the prophet Mohammed hang in every classroom. Children must wear uniforms: long shapeless robes and head scarves for the older girls and neat blue sweaters and gray trousers for the boys. Besides their regular studies, students take two classes a week in Islamic studies and three a week in Arabic, the language of the Koran.

A glance at Al Iman's handbook for students and parents further underlines the differences from public schools. The rules are strict: three demerits for taking toys, comics, cosmetics, jewelry or other unauthorized materials to school, one for wearing nail polish, five for disrespectful behavior to teachers or for "pursuing acts of romanticism" like flirting with a schoolmate. The punishment for five demerits is detention during lunch for three days. After 30 demerits, a child is suspended for a week, and after 40, expelled.

For students who transfer from public school, the transition can be difficult.

"My parents insisted I come here and I didn't really argue with them," said Amel Ahmed, 17, whose parents emigrated from Yemen in 1980. She admitted she had picked up some bad habits in public school, but said the individual attention and strictly enforced regulations at Al Iman had set her straight.

"I wasn't on the right track there, maybe because you get influenced by your friends," Amel said. "Here they don't only teach you. They guide you."

Until recently, a full-time academic course load combined with Islamic teaching was available mainly through the national network of Sister Clara Muhammad schools, named for the wife of the Nation of Islam's founder, Elijah Muhammad, mainly serving African-American students. Two in New York City have been operating since the early 1970's, although they are no longer associated with the Nation of Islam. Now a new type of school serving a broader group of Muslims has emerged. In a sudden growth spurt, the number of Islamic schools nationwide has jumped to at least 200, according to the Council of Islamic Schools in North America, an informal body that sponsors workshops for Muslim educators. But neither the council nor any other group keeps official track of school openings, and American Muslims say they believe that the national figures are even higher.

|

Al Noor School in Brooklyn and other Islamic schools offer religion and Arabic classes with a standard academic curriculum and use a formula of piety and penalties. |

As recently as three years ago, fewer than 200 children in New York City and Long Island attended private Islamic schools. Today, with two full-time high schools in Queens and plans to build three more in Brooklyn and Manhattan, total enrollment is 2,400 spread among 13 schools, with the majority of students from immigrant families. In New Jersey there are now at least 10 private Islamic schools, not only in big cities, with their notoriously troubled public schools, but also in small towns with respected school districts.

Private school enrollment is up in general, and many of the attractions are the same for all parents, Muslim or not, who view public schools as too permissive, rowdy and crowded.

But a more subtle dynamic is at work in the national surge in Islamic private schools. It represents a coming of age, in the view of many Muslim leaders, for a community striving to define itself as a cohesive religious minority in the secular American society.

Long a community of distinct and often introverted parts, Muslims have begun a process familiar to many immigrant and ethnic groups. They are trying to reach beyond their internal demarcations of national origin and find a unified voice to defend and promote their interests in a multicultural society.

Convinced that many Americans have a distorted view of Muslims and their Islamic religion, compounded by images in the movies and the media, they have created national organizations, lobbying groups, voter-registration campaigns and outreach programs to explain Islam to their neighbors.

Those who help to create a school system see themselves as an integral part of this communal effort to define, for themselves and for others, what it means to be a Muslim in the United States.

"My father's family survived in Bosnian society as a minority for centuries," said Saffiya Turan, a founder of Noor al Iman School in South Brunswick, N.J., whose father emigrated more than 30 years ago from Yugoslavia. "To survive, you have to know who you are."

The challenge for Islamic educators is to create a spiritual educational experience for young Muslims that is also relevant to their lives in a secular society. It has been a process of trial and error, ad-libbing and self-discovery.

Many schools cobble together teaching materials from other countries. Abuasi, who is Palestinian-American, said he experimented with books from Egypt, Yemen and elsewhere before settling on Arabic texts from Jordan to teach the Koran, which Muslims believe is God's word as transmitted to the prophet Mohammed.

At Noor ul Iman School in South Brunswick, one teacher, Abir Catovic, decided it made more sense for American schools to write their own texts.

"Overseas, you aren't taught to ask why," said Mrs. Catovic, 31, who grew up in New Jersey after her family emigrated from Egypt. "Here you've got students who ask why, and you'd better be prepared to answer more than just, 'Because it says so.' "

Religious schools for American Muslims also have to contend with a widely diverse student body. At Al Iman in Queens, for example, any one class might have children from Egyptian, Yemeni, Pakistani, Indian and African-American backgrounds. For Souhair Ayach, who teaches Islamic studies, having that mix of cultures requires her constantly to stress the difference between old country traditions and religion.

One recent day, Ms. Ayach's class strayed from a discussion of the divine source of human genius to a more worldly topic that was on the minds of her 11th- and 12th-grade students: arranged marriages.

"Is there something in Islam that, like, says a girl should get married at a young age, or is it just tradition?" asked a teen-age girl who gave her name only as Sabih, whose parents came from Pakistan but whose accent announced her New York City upbringing.

Ms. Ayach, herself a recent immigrant from Lebanon, steered a cautious course. "In the past, people had everything they needed to live," she said. "They were shepherds. They were merchants. They had castles. They didn't have all these expenses of life.

"Here," she continued, "you have to have education because you need a good job, a respectable job, to make your living. So it's better if you marry early, but under some circumstances it's better to develop your life first."

Private schooling still touches only a small portion of American Muslims, whose numbers are growing. There are no official national figures, but a 1992 study commissioned by the American Muslim Council, a lobbying group in Washington, estimated the Muslim population in New York State at 800,000 and in New Jersey at 200,000. A more recent study by demographers at the State University of New York at Cortlandt concluded that 450,000 Muslims live in the New York metropolitan area alone.

Islamic schools are still small players in the private-education business. In New York State, 480,000 students, 1 in 5 of school age children, attend one of 2,400 registered nonpublic schools, most of them Roman Catholic schools or Jewish day schools and yeshivas.

But Muslim educators say the numbers of full-time Muslim students do not tell the complete story. Many of their schools have only now reached a point of critical mass at which they can attract more students because they offer advanced grade levels and have a demonstrable academic track record.

Still, it is difficult to gauge the real demand for Islamic schools, most of which charge up to $3,000 a year in tuition. But school administrators say that in an area that already supports 450 mosques in New York City and Long Island, there is a vast untapped pool of families willing to pay for an alternative to the secular public schools.

"This year we added 140 students from the public schools, all coming with the behavioral and academic problems they inherited: name calling, taunting with labels and names, casual profanity," said Abuasi at Al Noor. "Here they have to watch the way they walk, watch the way they talk and watch what comes out of their mouths."

The formula of piety and penalties at schools like Al Noor seems to have whetted the appetite of Muslim parents. Al Noor opened only three years ago, with an initial enrollment of 350 students in six grades. It now has 600 children from prekindergarten through ninth grade and is raising money from Arabic and Muslim businesses in the area to build a $4 million addition to the school.

To meet expected demand in Manhattan, the Kuwaiti-financed Islamic Cultural Center of New York is building a $10 million, five-story school for 1,000 students, next to its complex at Third Avenue and 96th Street.

Al Farooq mosque in Brooklyn, one of the busiest in the city, is soliciting donations to convert its top four floors into an Islamic junior high and high school for girls.

Abdulhakim Ali Mohamed, the imam at the mosque, said the need for a girls' school is particularly acute in his neighborhood of immigrants. Families from conservative Arab countries abhor the mixing of boys and girls in public schools, he said, and panic when their daughters become teen-agers.

"Many are thinking of sending them back home," Mohamed said. "We tell them that's not a solution. If you take them back, you have to go back with them."

Like new immigrants, more established Muslim families worry that their children may lose their religious identity or do poorly in public schools where their dress, holidays and religious taboos can make them curiosities.

Dawn El Mezyen, a convert to Islam, tried to help her son fit in at a conventional kindergarten, at one point acceding to his pleas to join in exchanging Valentine's Day cards with his schoolmates. It took hours, she said, to sort through piles of store-bought cards and toss those with romantic messages she believed were inappropriate for a Muslim boy to give.

Then she transferred him to the Noor ul Iman School in South Brunswick, N.J. "I needed him to be around other Muslim kids," Mrs. El Mezyen said. "I wanted it to be a day to day thing. I didn't want him to be the sore thumb that sticks out. Here we all celebrate a holiday together."

At Al Iman School in Queens, robes are required and cosmetics, jewelry and flirting are forbidden. |