Our thanks to "Queen Arawelo, the original

Somali feminist" for everything on this page.

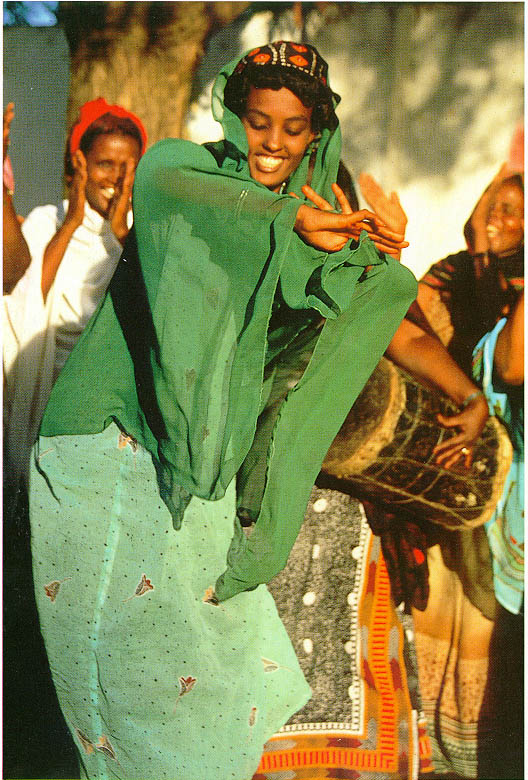

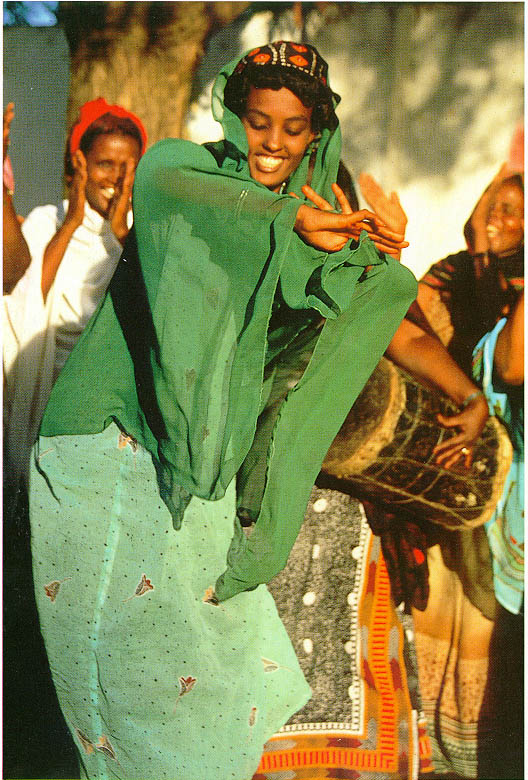

Hooyo Hooyo

Hibo iyo Ducaba Naga Hooyo

Hooyo Hooyo

Hibo iyo Ducaba Naga Hooyo

Wiil iyo Caano Naga Hooyo

These blessings have been bestowed to the bride and bridegroom

since time and memorium. Marriage in Somali culture has always

been a cornerstone of society. It has signified not only a union

of two young people but also of two families and most of the

time, two clans. Over the last ten years, due to the instability

and crises at home, many Somalis fled and settled in foreign

lands. As a result, marriage itself has also been affected as

changing roles and expectations enter the picture.

For more information about Somali culture, including a discussion

forum, see Queen

Arawelo's Palace.

Somali Marriage in Colonian Culture

by H. RAYN E. (Editor's Note: This article was written

in 1920 by a non-Muslim observer)

SOMAL marriage laws are practically Muslim marriage laws,

with a difference; it is this difference that makes them so interesting

to study. A man may have four wives, with all the trouble he

deserves in consequence thrown in. He may become engaged to a

girl before she is born by making an arrangement with her "

prospective "-for want of a better word-parents. The engagement

in any case is always arranged between the girl's parents or

guardians, and is clinched by a small present from the man to

them as a token of finality. This token, which may consist of

a horse or even any small personal possession of the man's, once

accepted makes the engagement binding for all time. If broken

by either party something like a breach of promise case is the

result. Any time before the marriage, property (generally in

the shape of stock) is paid by the suitor to the parents as the

purchase price of his bride. The value of this property varies

among different tribes and for different women. If before marriage

a girl dies, her relations must return the purchase price paid,

which is called yarad. Should the man die his next of kin may

marry the girl on making a small further payment. Should she

refuse this alliance another must be found to take her place,

or the yarad be returned to the deceased's estate.

If everything is arranged satisfactorily and the marriage

be consummated, a substantial proportion (known as dibad) of

the yarad is returned to the man by his wife's people. The marriage

is generally celebrated by a Kathi or Sheikh, and at the ceremony

the amount of dowry-or mehr, as it is called here-to be settled

on the wife by her husband is recorded. The mehr may consist

of anything-generally stock-and need not be paid at the time,

but it is a very important matter for the woman that it be clearly

defined. Should she be divorced her husband must hand to her

the mehr agreed on at the marriage ceremony. Should he die she

has first claim on his estate for her settlement, which is quite

apart from any subsequent share of the estate she is entitled

to as deceased's wife. However, should she refuse to marry her

deceased husband's next of kin or a man of his tribe chosen by

his people, she forfeits all rights to both her mehr and share

of the estate. This is roughly the basis of Somal marriage laws.

The following literal copies of correspondence gives some idea

of how it works out in practice.

Letter from Abdillahai Deria of the Arab (Somal) tribe to

the District Commissioner of town X-, dated 20/II/18.

" I beg to inform your honour that a woman called Atub

Handulla, of the Habr Yunis (tribe), Idarais (section), was married

to my cousin Ismail Haid, Arab, Gulaneh, who died about six months

ago. We have given her all her mehr and paid yarad to her uncle

Farah Aman, Habr Yunis., Idarais. The woman said that she wants

to go to town Z-to bring all her furnitures and sell her ariesh

(native house), but it is now heard that some one is going to

marry her at Z . I therefore pray your honour may ask the District

Commissioner at Z to send her to X . By granting the above request

I shall ever pray for your long life and prosperity."

The D.C. at X sends a copy of above to the D.C. at Z-, minuted

" For inquiry and return please." The latter sends

the following reply:

" The woman Atub Handulla states: ' On hearing of my

late husband's death I went to X to see if any of his tribe wished

to marry me. When I got there no one wished to do so and I was

unable to get any support from the tribe. I could not complain

to the D.C. as he was away from the station, but I went to the

Kathi and he told my husband's tribe to pay me money for maintenance,

which they refused to do. I therefore came back to Z where I

have lived all my life and where I have a house. I am quite ready

to be married to any one of my late husband's tribe and would

ask that any one who wishes may come to Z to fetch me. Of the

people of this tribe in Z no one wants to marry me." Dated

at Z-I0/I2/I8, No. 56/I8.

It looks very simple on the face of this, and back comes the

following from D.C., X--

" With reference to your No. 56/I8 of 10th December, the

Akil Jama Awit will send Kahim Elmi, Arab, Gulaneh, to marry

the lady. Dated X , 7th January, 1919."

It is evident from above that Kahim Elmi has been selected

by the deceased's relatives to marryAtub Handulla, an arrangement

she ought to agree to as she has evidently been paid her mehr.

Though it does not transpire who he is in the correspondence

as yet, Kahim is probably a cousin of the deceased. The next

letter is from him to the D.C., X , and proves I am right in

my supposition. It is in the same strain as the one addressed

to the same officer by Abdillahai Deria and is not worth repeating.

It is sent on to the D.C. at Z with a memo requesting him to

send the woman to X as Kahim Elmi is now too sick to travel.

The D.C., Z-sends the following reply:

"With reference to your minute No. 95, the woman Atub

Handulleh left for Jibouti when she heard that she would be required

to go to X-."

This last letter is dated March 11th, 1919, so time has been

passing and the matrimonial affairs of Atub Handula (I stick

to Abdillahai Deria's spelling) are no nearer settlement than

they were last year. The next letter addressed to D.C., Z- discloses

the name of the person from whom Abdillahai heard the woman was

going to marry some one at Z-. He is a relation of the deceased

and a policeman at Z . Apparently the lady, on the strength of

his relationship by marriage, has induced him to provide her

with food, for which expense the second man to marry her is ultimately

responsible. As she has gone to French territory it appears to

him that he may whistle for the money he has spent on her, but

is he downhearted ? No ! He writes the following to the D.C.

at Z-.

" Re Atub Handulla's case who fled away to Jibuti I most

humbly beg to state that I was maintaining her for the last two

years, when her husband in Tripoli and dead there. As her husband

was of my relation and she promised to pay me musruf [maintenance,

return of, is meant] when her husband came down to or from his

relations. Now she refuses to marry to my relation and she promised

to pay me musruf but fled away to Jibuti, all this done by mother

of woman, I had paid her the following: 4 of « tobe mahmudi

[cloth] Rs. I6/-, 5 nos futa [defeats me] Rs. 29/-, and on her

departure now to Jibuti she took the following clothes and Icash.

Cash rupees ten, 5 lbs. ghee, one futa value seven rupees, «

tobe Rs. 4/-, and three gallons of water daily for two years.

As if the said woman is willing to marry to one of my relations

I shall not claim for the above articles, if not I want my claim

from her or from the man who will marry her. And the man who

going to marry her is a policeman in French service."

It might be as well to explain that water is carried some

miles into I, where there is no water supply, and is an expensive

item. The lady has had a daily supply for the past two years

is what is meant above, and has gone off without paying for it.

The policeman four days later, 12th April, reports that Atub

has returned from Jibuti, so we have not seen the last of her

yet. She has heard of his letter to the D.C., I, and counters

with the following:

"To the D.C., Z-,

" Reference to the complaint filed against me by a policeman

I most humbly beg to state that I was married to one Ismail Haid

so he was absent three years in Tripolis and about eleven months

ago he died and since that time no one of his relations paid

me a single pie. Then his property was sent to X , so I went

for my share and mehr and I was given one hundred rupees in mehr

and one hundred and twenty is still due by his relations. My

late husband have no nearest relations at all, and at that time

I was at X no one come to complain against me so I proceed to

I. As since my husband's absence at Tripoli my mother was maintaining

me; also I am indebted to several people here, but if the complainants

will pay my balance of mehr and settle my debt I shall go with

them. I therefore request your honour to consider my claim fully

and grant me justice as I am an orphan woman and have no one

to complain to him or help except your honour. As my late husband

had married me at Z and I came here when I was two years old.

By doing me this act of kindness I shall ever remain grateful."

The D.C. thought now that the lady had returned she might

come to court and explain certain matters that required clearing

up. She came, and the following letter addressed by the D.C.,

Z to the D.C., X explains what happened at the interview.

" In reply to your minute No. so and so, Atub Handullah

is an epileptic or at least suffers from fits of some kind, and

is quite unfit to travel to X-. I do not think Kahim Elmi can

be aware of her state of health or he would not want to marry

her. So far as I can make out he does not stand to gain financially

by this marriage. Will you communicate these facts to him and

let me know what he wants to do about it.

" P.S.-Since writing the above the woman has had a fit

outside my office. It would be perfectly impossible to send her

to X --."

It is obvious from above that the D.C., is getting more than

a little tired of Atub and her affairs, but he has not heard

the last of her yet. Nevertheless I shall be very surprised if

she marries Kahim, and the odds are she sticks to the mehr. As

for the policeman and his claim he has given up hope; but he

smiles if any one mentions the fact that poor Atub suffers from

fits.

The Somal has some conceit as to his ability to understand

the fairer sex. The following story was related to me as illustrative

of this claim and concerns a man who had four wives. One fine

day this fellow came to town to sell his ghl and a few head of

cattle. Before setting out for home he purchased a present for

each one of his wives. For the first he bought a silver necklet,

for the second a pair of silver earrings, for the third a silver

armlet and for the fourth a silver anklet, tying the four articles

up in a parcel which he placed on one of his camels. Of the rice,

dates and sugar he had bought he made four equal loads, one for

each wife. Coming close to his encampment he took the silver

articles from the camel's back and hid them in the bush. This

done he went on to his wives and gave each one her load of food.

That night when darkness fell he stole out to the bush and took

from the parcel the silver necklet. Returning to the hut of wife

number one he said to her: " See ! Here is a present I have

brought you from the town: take it, but on your life keep it

secret from the other women, or they will be jealous." She

promised not to show it to the others or say a word about it.

The following night he repeated his visit to the bush and returned

to the second wife with the earrings, which he gave to her, saying:

"Here is a present I have brought you from town, on your

life do not show it to the others or they will be jealous."

She promised to keep the present secret. On the third and fourth

nights he went to the bush and brought back the presents he had

purchased for the other two: They were both cautioned not to

tell the others and both promised not to do so. Each wife was

under the impression she had received a present from her husband

and the others had received none.

A few days passed without incident, until one evening some

trivial thing happened that upset the women and there was an

open rupture between all four wives. Next morning the first wife

arose with the fixed determination to show the others that in

the eyes of her Lord and Master she was still number one. She

clasped the silver necklet round her throat and walked into the

open: striking an attitude, she ostentatiously played with the

ornament as she called out to a small boy: " My son, drive

the camels out; drive the camels out; do you hear me, drive the

camels out.' " But almost simultaneously the second, third

and fourth wives appeared on the scene, one shaking her head

to attract attention to a pair of earrings; another pointing

her hand and waving an arm adorned by a silver armlet; another

screaming out for the love of Allah that some one would come

quickly to remove a thorn she thought had entered her foot, held

out for inspection, and above which glittered a brand new silver

anklet for all the world to see. Then the women looked at one

another and realised they had been hoaxed: their husband laughed

in his beard and walked away. Now that's the only part of the

story I can't believe. I mean that the man walked away. From

what I know of Somal women I am positive the husband of the four

wives left very early in the proceedings- RUNNING.

It often happens that women contract bigamous marriages. A

French Somal soldier under orders for Europe left his wife (at

Jibuti) an allotment of three dollars a month and sailed away.

Another Somal soldier became acquainted with the lady and, unaware

of the first husband's existence, married her. He too was ordered

to France, and left her an allotment of three dollars a- month

ere he sailed. Then a third soldier appeared on the scene and

married her before he left for France, also leaving her an allotment

for a similar amount as the others.

On pay day the woman veiled her face and collected three allotments.

All went merrily until one day the three husbands returned from

the war on the same ship. When they could get away they naturally

went to see their wife, arriving at her house at the same moment.

The real husband wondered why the other two men looked like taking

up their quarters in his wife's house. They, as a matter of fact,

were thinking along precisely the same lines as he. After a time

some one suggested all three men should repair to a cafe for

a cup of coffee; each thinking it was an excellent opportunity

to get rid of the other two, readily agreed. Leaving the coffee

shop they said good-bye to one another, and carefully separated.

When out of sight of each other they all turned and headed for

their wife's house, arriving there at identically the same moment.

The woman had to make a clean breast of it; a fight ensued and

one of the men was killed, the woman barely escaping with her

life.

One last story of a marriage complication. In Berbera court

a tall fine-looking Somal soldier from Jibuti complained against

an old man who had accepted a yarad from him ere he left for

France two years or more before. The yarad was paid for a daughter

who was in the court with the old man, but both stated the soldier

was mistaken as to the girl's identity. He was, they said, confusing

the girl in court with her sister, whom he had betrothed and

who was perfectly willing to marry him. The soldier smiled and

swore he was making no mistake.

The father was asked to swear a divorce oath that he had not

betrothed the daughter present in court to the soldier. He refused.

The girl likewise, although very voluble, refused to swear an

ordinary oath that she was speaking the truth. It was obvious

they were both lying. As the man was wearing the Medaille militaire

and the Croix de guerre with palm-leaf, we had made inquiries

and learned he was the first man into the German trenches at

the retaking of Douaimont. The D.C., pointing his finger at the

soldier, said to the girl: " It is obvious to me you are

not speaking the truth. Here is a fine fellow who has made a

name for himself, and whom any girl might well be proud to marry;

a man whom the General picked out and decorated, before the whole

army, for magnificent bravery: God knows how many men he has

killed with his bayonet. You must keep to your contract."

Then the girl swore. Straightening herself up, she declaimed

passionately that the man she loved and was going to marry had

killed two men for every one THIS fellow - with a contemptuous

sweep of her hand - had killed. As for bravery, he - snapping

her fingers in the soldier's face - was not to be compared with

her man. Dropping the tobe from her shoulders she wound it round

her waist like a scarf, and holding the ends with both hands

swore by everything a woman can swear by that she'd marry her

own man and no other. What could the poor D.C. do but send them

all out of court to settle the matter amongst themselves. I never

heard the end, but were I a Somal I should have no hesitation

in swearing blindly any kind of oath that that woman got her

own way.

African Society Journal,

VOL. XX No. CXIV., 1920, pp.23-30. |

BACK

TO WEDDING CUSTOMS

BACK

TO WEDDING CUSTOMS